The week the pandemic revealed the heart of the hospitality industry

Supporting Marcus Rashford’s campaign for free school meals - the story of a family-run business offers lessons and inspiration.

Victoria Brookman is an On Purpose October 2019 Fellow, who completed placements at NEL Healthcare Consulting and the National Citizen Service Trust, and is now working in healthcare innovation. She interviewed Malachy O’Keeffe, Marketing Manager at Pho.

It was 5pm on the Friday before half-term this last October. The government had voted earlier in the week against extending free school meals over half-term holidays. Malachy O’Keeffe, Marketing Manager at Pho restaurants, had just gotten approval to give away thousands of meals to children in need across the UK who, from Monday, wouldn’t be able to get the lunches they usually relied upon at school. This proved not to be as easy as it might sound. But the weekend and week that followed left O’Keeffe with useful learnings about the importance of quickly adapting to local needs, a renewed sense of inspiration in the power of the people’s voice to make change, and reflections on the fundamental role hospitality continues to play in communities.

Local businesses rally behind Rashford to tackle food poverty

During the summer of 2020, English footballer Marcus Rashford successfully forced a government U-turn over provision of £15-a-week free school meal vouchers, receiving an MBE for his efforts just before his 23rd birthday. Families who normally rely on free school meals during term time for their children (about 17.3% of state-educated pupils in England as of January 2020, and closer to 1 in 4 in some areas) have faced a particularly difficult deficit during school holidays and closures throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The Trussell Trust, the UK’s largest food bank network, saw a whopping 95% increase in emergency food parcels given out to households with children in April 2020 compared to April 2019, representing a far greater increase than in other groups.

By October, with half-term looming and a government refusal to extend the meal voucher scheme over the holiday, Rashford found himself launching another campaign in pursuit of the same goal.

In response, and despite great financial challenges of their own as a result of several lockdowns, a wave of thousands of local businesses across the country offered to provide free meals to children in need.

Malachy O’Keeffe, who was part furloughed at the time in his marketing role at Vietnamese restaurant business Pho, tells me in our interview over Zoom that he remembers the feeling of a groundswell of support blooming. “It was one of those real things where you could just tell everyone was galvanized, and it was infectious.” O’Keeffe, now based in London, grew up in the West Midlands. He knew how important free school meals were to kids living in food poverty, owing to his prior experience working for SHINE, a charity based in Leeds that helps raise the attainment of disadvantaged children in the North of England.

So on Friday morning, he came to his boss and said that they needed to do something. By the end of the day, he had written up a proposal to give away 50 meals per day from each Pho restaurant across the UK, and gotten it approved by Pho’s owners - a feat he attributes to how a small, passionate, family-run business works.

Not your typical weekend

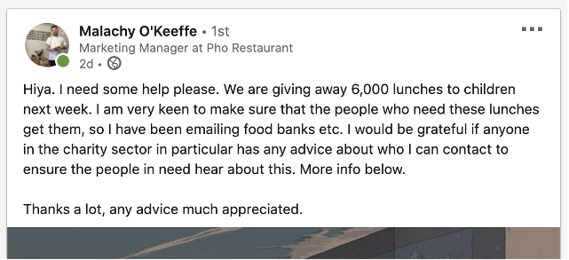

Monday was the start of half-term, so O’Keeffe got to work with his arsenal of marketing tools. Starting on Friday night, he set about contacting as many food banks and local charities across Pho’s 25 open locations across the UK as he could (Pho has 30 restaurants, but 5 were closed at the time due to COVID-19 impact). Appealing to his network of charity workers from his previous experience and food bloggers and influencers from his time in hospitality, he put out a post on LinkedIn asking for advice on how to get the food to where it was needed most. He set up messaging on Pho’s website and social channels, and started picking up the phone. “I contacted literally everyone I knew.”

His posts were quickly flooded with comments and tags. “By 10 o'clock on Saturday morning, I was having phone calls with people in London, Cambridge, Oxford, where I was saying, right, what do you need? Who are you? How can we help?” He toggled between phone calls, instant messages, scraps of paper, and a giant spreadsheet, collating names and details of organisations in 25 areas across the country.

He remembers being particularly heartened by how helpful LinkedIn turned out to be, because of the manicured way many of us tend to use professional social platforms. “We all know that in people’s LinkedIn personas, [they] hype up a totally different part of themselves, their ultra-corporate, shiny aspects; it lacks a little bit of the normal stuff, which I think is most important.” O’Keeffe was blown away by the barrage of supportive and useful comments he received, both from people he knew well and people he’d barely spoken to before.

By Monday lunchtime, Pho had partnered with several charities ready to take food and put it to good use, and had put the word out through local newspapers and other channels that each restaurant was ready to hand meals directly to families who were welcome to collect them without questions asked.

Monday came, and there was more work to be done.

Adapting quickly to need

Whilst Pho was pleased to see many individuals and families taking up their offer, direct collections of meals from some of their restaurants didn’t occur to the degree they had expected. It likely wasn’t always going to be practical, O’Keeffe reflected, for families in need to get to a restaurant in the centre of town and pick up a meal, for a variety of reasons - if they had even managed to successfully get word of the resource.

Additionally, most food banks as well as some charities, essentially told O’Keeffe: okay, it’s great that you’re giving away hot meals, but that’s not what we actually need.

So, O’Keeffe and his colleagues adapted.

In situations where a prepared bowl of steamed vegetables and fried rice didn’t work for the models of food distribution that an organisation needed, O’Keeffe worked with store managers to figure out what raw ingredients their budgeted meals amounted to, and improvised the operation to give away kilograms of rice, peas, sweetcorn, and eggs. These ingredients could then be put together at other sites before going to families in need. Pivoting to this model in some locations allowed Pho to partner with FareShare, a charity network tackling hunger and food waste supported by Marcus Rashford, and with The Felix Project, a London-based charity that redistributes surplus food to charities.

The team at Pho worked harder to partner with local charities and community groups who could put large quantities of hot meals to good use quickly, and couriered deliveries if the meals couldn’t be collected in store. In Oxford, not-for-profit Oxford Community Action, who have supported marginalised and hard to reach groups in need of food supplies during the pandemic, distributed 50 meals a day from their local Pho to groups of children they were hosting for half-term events. In South London, Brixton-based Football Beyond Borders was able to offer Pho’s meals at their community centre and at a youth football tournament. Further west in the capital, Solidarity Sports provided the Vietnamese meals to local kids attending a sports week, and used the opportunity to talk to its young athletes about different cultures and foods. The fact that the pitch was located minutes from the massive Westfield London shopping centre, a micro demonstration of the kind of stark disparities in our society that Marcus Rashford had been raising awareness of, was not lost on O’Keeffe.

Listen to the experts on the ground, and be humble

What worked in the end for Pho was an individualised, flexible approach that listened to local need, rather than forcing a blanket solution that didn’t work for all of its beneficiaries. O’Keeffe appreciates this user-centred approach from his background in the charity sector. “Whenever you're doing something CSR-related or something community focused, I think a lot of organisations want to do something that makes them look amazing and fits the brand, but ultimately, you need to do what works for the charity. So if the charity say I don't want 10 hot meals, I want enough ingredients to make X amount of meals in a week, then just do that, you know? It's simple.”

The team at Pho also humbly deferred to the expertise of organisations on the ground and embedded in their communities. “The real superheroes were local community action groups, local charities, local people running half term provisions for people in their community. There are just people around you doing amazing work, who you probably wouldn't notice or see on a day to day basis. And they're the experts, you know? They're the people who know what the community is like and what it needs. We're not experts in accessing these children or families, whereas they are. I think trying to partner and speak to those people as quickly as possible is the best way to make an impact,” says O’Keeffe.

By being flexible and partnering with local experts, they could remove barriers to access and ensure the food was actually going to people that needed it, which was Pho’s key objective.

In the end, Pho was able to give away over 3,000 meals to children and families over October half-term. O’Keeffe is quick to share the credit. “Totally, totally the success of the week is down to the work of the local charities we partnered with, to ensure that the food went to the right places.”

The power of communities and campaigns to make real change

In the course of the week, O’Keeffe was buoyed by seeing so many local organisations swiftly step up and support their residents. “It was just so heartening to see how quickly communities came together,” he remarks. He recalls an example of a pub sending its staff to Tesco to pick up ingredients and then calling in its regulars to come and help make packed lunches for kids in the area; he notes an instance where a teacher from a local school collected meals from a Pho restaurant and helped deliver them to parents and children herself.

These reflections from O’Keeffe didn’t surprise me given how he’d described Pho as an organisation earlier in our conversation. Pho is still run by the husband and wife duo that set it up 15 years ago, having been enamored with the fresh, healthy Vietnamese street food they encountered on a trip there. As part of his role as marketing manager, in pre-pandemic times O’Keeffe would walk around a neighbourhood where Pho had opened up a restaurant, meeting people, developing relationships, and getting to know their neighbours.

In that same vein, O’Keeffe opined that the week’s actions shone light on the real meaning of hospitality. “‘Hospitality’ is welcoming someone into your house, your home, giving them food, giving them drink, and making sure they have a nice time and are looked after,” he said. “That's what everyone in every pub, restaurant, or cafe in the country cares about. And this has really illuminated that this is what we are and this is what we do, and we are there for the communities. I really think the industry has just stood up so proudly in a really horrible time and said, we will look after people who need it. And that, to me... it feels great to be a part of an industry that does that kind of thing.”

Not that he’s saying that these institutions should have to keep doing this. Indeed, he emphasises the impactful policy results that the actions of individuals and communities across the country made: in early November, Boris Johnson announced in a phone call to Marcus Rashford that his government would extend food programme funding for vulnerable families in England over school holidays through 2021 in an effort to address child food poverty. For O’Keeffe, this U-turn in government policy shows “how the power of campaigns and the power of people coming together really does work… without Marcus Rashford, without every single pub, cafe, mom and pop shop that did this, it's hard to know if they would have changed that policy. And I think that for me is the big deal.” However you interpret the motives behind the government’s decision, he continues, “it's good for the kids who are going to get fed. And that's all that matters.”

O’Keeffe will remember the show of solidarity he experienced first hand this past autumn as a source of hope and inspiration. He concludes: “The voice of the people still counts, the work that communities do together still counts, and it can change a lot. This stuff still works.”

Images: @MarcusRashford, Twitter post (Oct 22, 2020, 10:30pm) and Malachy O’Keeffe, LinkedIn post (Oct 23, 2020).