Up for debate: The right to protest and how we can protect it

The right to protest is a fundamental cornerstone of any vibrant and tolerant democracy. We’ve all seen the important role that protest has played in movements, such as Black Lives Matter and the Iranian ‘Mahsa Amini protests’, to increase awareness around societal issues and assist in shifting public opinion. However, it has recently been up for debate in the UK, with the Government's proposal of the Public Order Bill currently in its final stages.

In light of this Bill, it’s more important than ever to understand what is at stake and what your rights are when it comes to protesting.

Why do we protest?

Throughout history, protest has been a powerful tool for change, leading to regime shifts and for many, increased freedoms. Protests have defined key historical moments, ranging from the Civil Rights movement to events such as the Arab Spring. The common theme of these protests is that they were led by those who refused to give up and who spoke truth to power. In recent years, protesting has continued to increase in prominence as a tool to voice key issues, such as austerity and civil rights, with the number of protests worldwide tripling from 2006-2020.

“I see it as a way to get our frustrations on the agenda and open up debate”

A core reason for protest is social unity. We believe that by coming together, we can address unsound elements in society and use the momentum of collective grievance and emotion to drive meaningful change.

“Protesting reminds me that I am not alone”

In more recent times, Teachers, Nurses, Civil Servants and many others shared that they saw protesting as the most effective way to amplify the voices of those who needed to be heard. By showcasing solidarity in these small, peaceful protests, we feel we have a magnified impact and see real change. Many people see protesting as a way to acknowledge and honour the privilege of having a political voice and view it as an important avenue to defend their continued right to that voice.

As Amnesty International states in their campaign, ‘you matter, and your voice does too’.

So what are the current laws around protesting in the UK?

In the UK, the right to peaceful protest is enshrined in the Rights to Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Assembly, protected respectively under Articles 10 and 11 of the European Convention on Human rights, which was directly incorporated into domestic British law by the Human Rights Act.

We have seen limitations to the right to protest in England and Wales introduced before, as set out in the Public Order Act 1986 and again in 2022 with the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act (PCSC). The Public Order Bill is looking to build on the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, but this time allowing for the measures to be debated in the House of Commons.

What is the Public Order Bill looking to introduce?

Some of key provisions the bill has put forward are:

- New protest-related offences for ‘locking-on’ e.g. a protester attaching themselves to other people, objects or buildings to cause disruption and ‘going equipped to lock-on’. Additionally, it looks to address disruption by tunnelling, obstructing major transport works, and interfering with key national infrastructure.

- Serious disruption prevention orders, which will allow courts to bar an individual from associating with other activists, being in a specific place, having particular items like bike locks or superglue, or encouraging others to commit a protest-related offence. They may be enforced by the imposition of an electronic tag, and breaches could lead to six months in prison or an unlimited fine.

- New stop and search powers for protest, which will allow police to intervene if they believe somebody has an object intended to help them to commit a protest-related offence like wilful obstruction of a highway.

Full details of the proposals of the bill can be found on the Public Order Bill factsheet.

Initial responses to the Bill indicate alarm around the proposals, with five UN Special Rapporteurs raising concerns that the Bill would seriously curtail human rights. Alongside this, the Index on Censorship ranked the UK as only ‘partly open’ and the Human Rights Watch warned that the UK was in danger of being added to its global list of human rights abusers.

Why does the UK Government feel the need to bring these measures in?

In response to recent protests, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said: “A balance must be struck between the rights of individuals and the rights of the hard-working majority to go about their day-to-day business.” Thus, the proposal of what the government has deemed “sensible and proportionate measures designed to allow the police to better balance the rights of protestors and the public”.

The government has used this Bill to particularly address Climate Protest, with the actions of protest groups such as Just Stop Oil and Insulate Britain being explicitly called out as part of the reason why the government believes it needs to act in preventing serious disruption.

Where is the Public Order Bill up to?

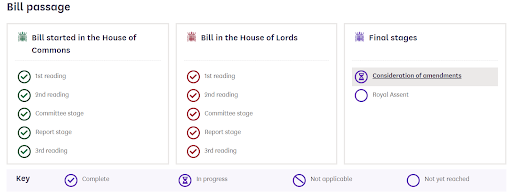

In mid-February, the House of Lords voted a total of eight times to block a series of controversial proposals in the Government’s Public Order Bill during the Bill’s Report Stage. The votes mean that some of the most extreme parts of the Bill have been thrown out for good. However, it is important to note that other anti-protest measures that were defeated could be reinserted into the Bill when it returns to the House of Commons.

Following the House of Lords review, the following anti-protest measures have been thrown out for good:

- Government amendments that would enable police to pre-emptively restrict protests on the off-chance they may become disruptive later on

- Government attempts to limit when someone can use the defence of ‘reasonable excuse’ when charged with wilful obstruction of the highway and other protest offences

MPs will vote again on the following measures:

- Addressing the proposed powers to stop and search protestors without suspicion

- Addressing the proposed powers to impose Serious Disruption Prevention Orders on people who have not been convicted of a crime

- Adding a definition of serious disruption in the Bill

- Narrowing who can be given a protest banning order on conviction

- Adding protections for journalists and other observers of protests.

So where do we go from here?

Undoubtedly, debates will remain for years to come around what constitutes an acceptable protest. However, what should not be up for debate is our right to peaceful protest. Protesting remains an important way to express and address issues, whether they touch on democracy, the environment or equality. So, in the words of Agnes Callamard, “it’s time to loudly remind those in power of our inalienable right to protest, to express grievances, and to demand change freely, collectively and publicly”.

The coming weeks will be a crucial time to influence MPs to ensure some of the most extreme measures are not amended and reintroduced in the Commons by the government. You can help by:

- Engaging with MPs to support the changes made by Lords, and encouraging those around you to also write to their MPs. Amnesty International has a template available here.

- “Nothing strengthens authority so much as silence”; If you feel comfortable to, please do use your voice and continue to amplify the importance of and raise awareness of the impact the Bill will have on people and communities playing an active role in social change.

Additional Information

For more information on how the new policing act affects may affect your protest rights, please see the following resources:

- Liberty: How does the new policing act affect my protest rights?

- Amnesty International: Protect the protest