How can effective altruism help you improve the world?

Having established in my previous post what I understand effective altruism (EA) to be, I now want to pose an additional question: How helpful is it as an approach? Here I’ll take each question from my previous post in turn and share my views. I’ve recently talked with several friends about their views on EA and I’ll also incorporate a few of their ideas. These were people who seek to improve the world in some way but who are not part of the EA community.

What is EA and why does it exist?

Effective altruism is an area of research and a social movement which seeks to find the best ways of doing good and put them into practice. It exists because there is an overwhelming amount of suffering in the world. EA exists so that we can help the most people to the greatest extent possible.

I agree with this goal. There is overwhelming suffering in the world and surely we should help to the greatest extent we can. That said, I understand that not everyone wants to pursue this goal all of the time. Humans have emotions, and sometimes we want to help a cause close to our heart or simply have fun. As an example, I volunteer at a soup kitchen and enjoy donating to friends’ sponsored swims. In these pursuits I expect I am not doing ‘the most good’ possible with my time and money, however, I’m still having some positive impact, and I believe that leaning into my passions is one powerful, sustainable way of making the world a little bit better.

Happily, calling yourself an effective altruist (or an “EA”) doesn’t obligate you to do the most good you can all of the time. Rather, EAs choose how much money and time they set aside for this goal of maximising their impact, and work as a community to figure out how to do this.

EA offers a clear, ambitious goal which I find motivating: Help the most people to the greatest extent you can. It does not stipulate how much of your time and energy you dedicate to that goal, but it does offer a community of people who are also integrating this goal into their wider life.

The friends I spoke to were largely very positive about EA’s aims. One said: “In terms of the goal of it, you’d have to be a moron not to want change...More effective use of resources - that’s got to be a good thing”.

However, many were sceptical about how the goal could be achieved. One said: “In theory it sounds nice I can’t really imagine how it works in practice”, while another agreed: “I don't understand how you determine the best possible thing? There are so many intended and unintended consequences of an action and you can't calculate everything. I don't know how you determine it - sounds great but how do you do it?”

What does EA do?

Effective altruism researches the best ways of doing good and puts them into practice. EA uses data to calculate how much a given option will help people, compares it to other options, and works to advance the option that helps the most people to the greatest degree. That might be through funding organisations, training people, or sharing information on the most effective charities.

This balance of careful research and action seems like a sound approach, however the emphasis on data and comparison is more complicated. Data can no doubt provide useful information, but can we really quantify how much a counselling session or malaria net improves someone’s life [1]? Our world is interconnected; we can’t ever know for certain what causes what.

This was a common sentiment among the friends I spoke to:

One said: “You can be improving one thing but making another thing worse. If you’re striving to improve the world you’re almost cancelling it out. It's great you've done one thing but if you don't think about it as a system you’re harming other things.”. Another summarised the situation simply by saying: “Sometimes something might help someone but not someone else”.

There is no denying that the world is complex. It’s hard to predict the consequences of an action and sometimes well-intended actions will have negative consequences. However, there is also no denying that the world is in a bad state. It’s hard to imagine that doing nothing will make it any better and carefully thought through actions can have enormous positive impact.

One friend summarised this balance well: “there’s a “stronger argument for using an EA approach for causes we could put a definite end to, for example the eradication of certain diseases. ‘Let's put all our resources in it for this period. We get rid of it, and then we can focus elsewhere’”. He contrasted this with: “if it's a type of issue which, because of the various effects and players and, you know, variables in the world could appear or disappear depending on what’s going on in the population, then it might be that actually without that holistic thing, that problem will only reappear later on.”

In the case of the malaria net, the evidence is strong. We know that malaria nets reduce malaria, and a lack of malaria means people live healthier, longer lives. Data suggests that distributing long-lasting-insecticide-treated nets reduces child mortality and malaria cases. This has led Givewell, an EA organisation, to recommend the Against Malaria Foundation as a top-rated charity.

Of course you need to be careful and thorough when weighing up the data: Are people using the nets correctly? Is the process of receiving a net a dignified one? Do you want to see people improve their health next year or can you wait ten or a hundred years? What other actors and factors are affecting recipients’ health? But these things all count towards how much the net helps the people, which is what you’re measuring, and careful measurements will do what they can to account for these considerations. Indeed Against Malaria Foundation conducts post-distribution surveys to see if the nets have reached their intended destinations and how long they remain in good condition, though the organisation admits there are limitations to its methodology.

So it seems the nets are effective at improving people’s health, but are they more effective than other options? Givewell states that net distribution is one of the most cost-effective ways to save lives they have seen. Their estimations suggest it costs $4,500 to save a life through a malaria net. Compare this with the cost of new cancer drugs - $45,000-$75,000 to improve someone’s health for a few years [3] - and the disparity is striking.

So, EA offers useful information for those wanting to maximise the impact of their donations. It is a simplification but it is a starting point. And it’s an important starting point - an individual could help 1000s more people simply by switching their donations - something which isn’t necessarily intuitive.

While Givewell is looking for the most effective charities, there is of course no objectively best charity since values and opinions are involved. In the malaria net example this could be the weight you place on individual autonomy. If you save thousands of people from malaria but they would rather have had some money to repair their roof, have you helped the most people to the greatest extent [2]? It depends on your views. Effective altruism attempts to navigate this space between fact and opinion, balancing the data with values and views on morality.

How does it do it?

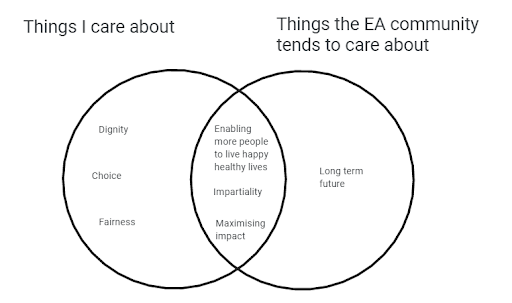

There are a couple of foundational premises. One is that doing good is understood to mean enabling more people to live happy and healthy lives. To me this is an acceptable definition but I don’t think it encompasses everything good. In my opinion, good might also include enabling people to have a comfortable death, creating a fair society, or promoting individual freedom. Of course not everyone would agree with my definition. Other people might say, for example, that experiencing art or preserving tradition is important. It follows that there are things I care about which effective altruism organisations are likely to care less about, and it is worth me keeping that in mind. However, what effective altruism does offer is a nudge to consider what I do care about, and to discuss it with people who are also pondering the question. How would you define “doing good”?

One part of this definition is who you care about. Here, effective altruism promotes impartiality. EAs attempt to value everyone equally no matter where or when they are born, and even what species they are. Personally, I aspire to follow this. I don’t think any group of people are superior to any other and I’d also put a decent weight on reducing animal suffering. But of course not everyone does, and I can understand their perspective. After all, how many chickens do you have to save to make it more valuable than saving the life of one human? How many cats?

My friends had strong opinions on this topic. One said: “Personally I’m only 100% interested in humans. I mean, I love watching David Attenborough and I’ll stroke nextdoor’s cats, but I would always prioritise humans”. Another disagreed: “I think I was born with the feeling that animals are just as important as humans.”

One group EA is increasingly concerned about is future generations. Longtermism is the view that positively influencing the long term future is a key moral priority of our time. At its simplest the argument is that humanity now has the capacity to destroy itself - significant threats include artificial intelligence, bioweapons, pandemics and nuclear. Currently very little is being done to prevent this and so EA sees it as a priority. I include this because a large portion of the EA community is focused on this work at the moment and yet it is not a mainstream idea. What’s your reaction to this? You might think: “Amazing, EAs have identified a neglected, important cause”. Or you might be less keen, worrying that time and money is being spent on speculative risks when there are many real life people suffering now. Data is available - for example, experts have estimated the risk from various threats - but again, values and viewpoints will play some role in the conclusion you reach.

On the whole though, working to enable everyone, no matter who they are, to live happy and healthy lives isn’t a bad way of going about things. As one of my friends put it: “It doesn't need to be debated too much up to a certain threshold… I think there's probably agreement on the fact that if you're in a state of extreme suffering, there's no way you can think about higher types of happiness without alleviating that suffering. And so I think that would be quite clear cut” .

If you largely agree with this idea, EA's recommendations are likely to offer you a good amount of guidance. You might see it as a Venn diagram. To some extent it doesn’t matter how big or small the overlap is - you can pick and choose the EA resources that are helpful to you.

Of course it’s more complicated than this and the effective altruism community recognises this. There are a plurality of viewpoints among the EA community In fact, they encourage members to debate and disagree and EA organisations will change their recommendations when new arguments and information is presented to them. EAs also try to adopt this mindset - changing their views constantly as they learn more. But who are these effective altruists discussing and forming views on what is good?

When, where and who?

The term was coined in Oxford in 2011, and nowadays EA is being applied by tens of thousands of people in more than 70 countries. Anyone can join from anywhere.

While in theory anyone can join the movement, it’s mostly young, white, highly educated men from the West who do join.

To me this is scary. If we stand a chance of working out good answers to such a difficult values-driven question as “how can we do the most good in the world”, I believe we need people involved with different backgrounds, viewpoints and ways of thinking. EA does not currently have enough of that.

That said, there are many ways anyone can get involved in effective altruism, and no prior knowledge is needed. EA has an active online forum which anyone can read and contribute to. It also runs free online courses, or you can get a free effective altruism book. You can sign an online pledge to donate 1% or 10% of your income and in doing so join a community of other people committed to this. In this sense EA offers community, guidance, challenge and support.

There are some efforts to make effective altruism more diverse and inclusive, however I believe EA needs to do far more. As one EA blogger, David Manheim, puts it:

“We want to make the world better, safer, and happier, and that means bringing the world along — not deciding for them. […] You don’t get to make, much less optimize, other people’s decisions”

David’s conclusion is that we should focus on broadening EA’s reach. He’s not saying EA is a bad thing, rather that it’s something that can be improved. Do I agree?

On balance, do I think EA is a good thing?

Perhaps I am trying to make EA something more than it is. It’s not a life philosophy asking everyone to strictly adhere to its principles and practices. At its simplest EA is a question: How can we do the most good possible?

I believe this is an important question, and I’m pleased to have found a community who are not only asking the question, but carefully trying to answer and act on it. It doesn’t have all the answers and some of the answers it does have I might not agree with. In these instances I might look elsewhere for answers - maybe to myself, maybe to friends, maybe to a book, or maybe to a different organisation.

Effective altruism desperately needs a more diverse community, it doesn’t offer universal values, and it can’t tell you what your personal passions are. But there is a lot in the community, resources and ways of thinking which I do find helpful. Here’s a summary of where EA might support those looking to make the world a better place.

Effective altruism can help you:

Adopt a good mindset

- Effective - how can I do the most good?

- Impartial - how can I value everyone equally?

- Truth-seeking - what do I believe to be true? Can I proudly change my mind when presented with new information even if that information is uncomfortable?

Donate more effectively

- Consider donating to one of Givewell’s top charities

- Consider donating 10% of your income, and benefit from a community of like-minded individuals

Learn more about effective impact

- Read an EA book

- Browse the forum or EA website

- Sign up for a free online 10 week intro course

- Reflect: What do I consider “doing good” to mean?

[1] We can at least give it a good go — Happier Lives Institute evaluates psychotherapy by looking at the effects on subjective wellbeing, while GiveWell has done a thorough analysis on the impact of malaria nets

[2] This is a hypothetical example. GiveWell surveys people in communities which are similar to those their top charities operate in. It asks survey respondents how they value different outcomes. However they have done only a limited amount of research and admit that its methods have major limitations

[3] It is estimated that new cancer drugs cost around $45,000-$75,000 per quality adjusted life year (QALY). QALYs measure both the quality and quantity of life lived. For example 1 year in perfect health equates to 1 QALY. 2 years at 50% health also equates to 1 QALY.