Pride Month 2021: Freedoms won and lost in the fight for progress

Emily (she/they) is an April 2021 On Purpose Associate, currently on placement at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Foundation where she is focusing on achieving health equity in urban environments.

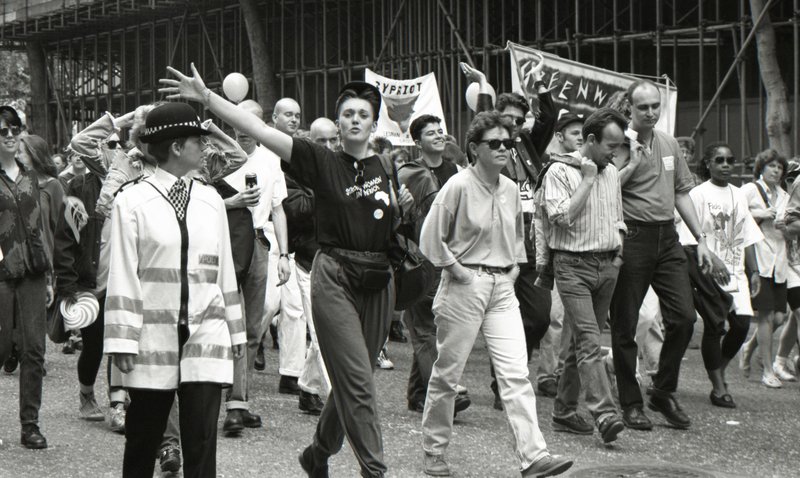

Last week, in the spirit of celebrating Pride Month, I went to see the film Rebel Dykes* at Genesis cinema as part of the Fringe! Flings series. The film centres around a group of South London-based sex-positive, lesbian, anarchist, squatter women living at the edges of the '80s' feminist movement, and follows them as they pull together (and fall apart) over identity politics and politics proper. The film itself is a riot of archive footage from club nights and political demonstrations, interspersed with interviews with the women involved in the movement and some comedic animations, and is definitely worth seeing if you can pin down a screening.

One of the things that struck me most from the film was that despite (and because of) the hostile political environment of the 1980’s (where homophobic attitudes manifested themselves in laws such as Clause 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 which essentially prevented schools from portraying homosexuality in a positive light, and in the Government’s response to the AIDS crisis) and the obvious risks associated with being visibly out as a lesbian at that time, the women interviewed were proud of their sexuality and used this to build community and find joy. They pulled together behind their identity and behind common political causes such as the anti-nuclear movement based at Greenham Common, the anti-Poll Tax demonstrations, and direct action against Clause 28, which provided them with a sense of purpose and belonging. The film also articulated the rifts that were present within these communities, such as the opposition that some lesbians felt towards the expression of BDSM practices at lesbian club nights, and presented the different ‘identity groups’ within the community as fairly rigid and fixed, with defining views, dress codes, and sexual practices.

Another thing that struck me from the film was the availability of affordable spaces to host these community groups and events, and which were central to this community-building, such as women’s centres, ‘women’s nights’ at welcoming pubs and clubs, and dedicated publicly-funded community centres such as the London Lesbian and Gay Centre on Cowcross Street. Easy access to social security benefits and grants available for education at the time also meant that people were able to live creatively in a way many of us can only imagine today; making art, music and taking part in activism.

All this got me thinking about the freedoms we have won and lost over the last 40 years. As mentioned by Patrick in his post for LGBTQIA+** History Month, there have been significant improvements in the UK for LGBTQIA+ people since the 1980s, and we are freer than ever to be who we are (although it is important to note that this doesn’t apply equally to everyone who comes under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella). Whilst labels and distinguishable groups still exist today in the LGBTQIA+ community, it is arguable that as society (and politics) has become more accepting of those who do not identify as heterosexual, there is a lot more fluidity under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella than there used to be. This seems to reflect an acknowledgement that identity and sexuality are not fixed, nor are they the only markers by which people define themselves, which arguably represents progress.

However, the blurring of identity lines seems to have simultaneously weakened those strong, community bonds that were central to achieving this progress in the first place. As stronger rights have been won at the political level by many groups under the LGBTQIA+ umbrella (for example, marriage equality) and being LGBTQIA+ has become more socially acceptable, the community is no longer united by the same common causes and no longer perhaps in need of the same type of LGBTQIA+ spaces, to the same extent.

This dissipation of the queer community has been compounded by modern politics, which has centred the individual rather than the community (resulting in a chronic underfunding of community services) and caused a serious housing crisis, characterised by huge rents on both private and commercial spaces, and a lack of availability of affordable housing. The effect of this has been the decimation of British nightlife, with huge negative implications for LGBTQIA+ spaces and events, and a decline in the cultural arts more generally, with people no longer as free to create art and live unbeholden to the economics of capitalism. Of course, LGBTQIA+ community space still exists in London today, but it does not exist in the same way that it used to; it lives online, and where physical spaces do remain (with a few exceptions, including the brilliant The Outside Project), they are commercial ventures, associated with nightlife and usually focused around the consumption of alcohol, which can be exclusionary for many.

Why does this matter? Well, for me, the answer was evident as I sat in the cinema watching Rebel Dykes, surrounded by others from the LGBTQIA+ community. It was the first time that I had been in such a space since before the pandemic, and the belonging and connection I felt from being in that space whilst learning about our shared history was so nourishing. Despite the rights the LGBTQIA+ community has won over the last 40 years, the fight for equality is far from over, particularly with respect to trans rights. Community, and physical spaces within which to build that community that is free from commercial interests are more important than ever if we are to continue to support each other and to fight for the rights and justice that our trans siblings deserve.

*Many of those in the film referred to themselves as ‘dykes’ which is a reclaimed term which politically has its own power when used by those individuals who have historically been called this as a slur. It is not a term which can be used by those outside of this community.

**I have used the acronym LGBTQIA+ as I believe it is the most inclusive term. My interpretation of this stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer or Questioning, Intersex and Asexual with the plus signifying the spectrum and diversity of Identity, Expression, Sex, Gender, and Sexual Orientation.

Photo by laury jaugey on Unsplash